The Truth Behind Mastering Mental Toughness

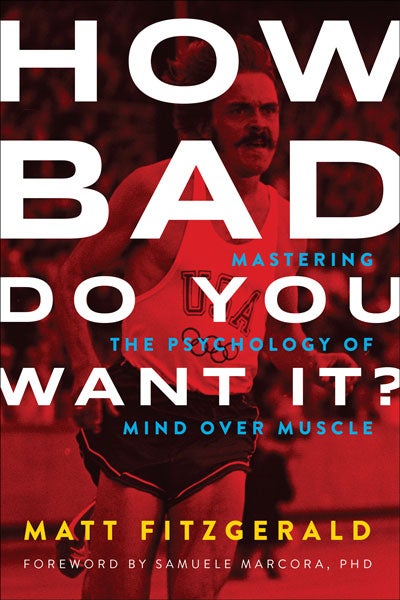

How Bad Do You Want It? Matt Fitzgerald

Republished from How Bad Do You Want It? Mastering the Psychology of Mind over Muscle by Matt Fitzgerald with permission of VeloPress. Learn more at www.velopress.com/howbad.

You never know how much your next race is going to hurt. Perception of effort is mysterious. You can push yourself equally hard in two separate races and yet somehow feel “on top of” your suffering in one race and overwhelmed by it in the other. Because you never know exactly what you’ll find inside that black box until you open it, there is a temptation to hope—perhaps not quite consciously—that your next race won’t be one of those grinding affairs. This hope is a poor coping skill. Bracing yourself—always expecting your next race to be your hardest yet—is a much more mature and effective way to prepare mentally for competition.

Jenny Barringer failed to brace herself for the discomfort she should have anticipated in the 2009 NCAA Cross Country Championships, and it doomed her. Her first mistake was looking past the race to the future. The meet in Terre Haute was to be her final encore as an amateur runner. Soon afterward, she would hire an agent, sign a big shoe contract, and embark on a career as a professional athlete. Although Jenny had chosen to return to Colorado for the 2009 cross country season to fulfill a promise and a dream, she was ready to move on—and in a crucial sense she already had moved on before her nightmarish last competition in a Buffaloes uniform.

She told Flotrack’s Ryan Fenton the day after the catastrophe, “A month or two before the race, I started saying, ‘I can’t wait for nationals to be over.’ I’ve never been like that before. I’ve always really looked forward to these events.”

In addition to looking past the race itself, Jenny looked past her competition. “That’s another mistake,” she said to Fenton. “I didn’t go out yesterday just to win. I had to break Sally’s course record and win by 30 seconds.”

No matter how much an athlete pushes herself in a race, to win by 30 seconds is to win easily. Jenny’s goals reflected an expectation of winning the race comfortably, in both senses of the word. This expectation was not unreasonable, as she had won every preceding event of the season without being challenged. But as a consequence of all this cakewalking, Jenny not only stopped expecting to suffer against college competition, but she also fell a bit out of practice with it.

It’s easy for experienced athletes to lose their appreciation for just how intense the suffering felt in races really is. They get used to it, which is a good thing, because getting used to suffering calluses them to it. But this tolerance only holds up when an athlete is properly braced. Any athlete who experienced race-level effort completely out of context would instantly regain full respect for its awfulness. If a runner were to suddenly experience the same level of effort she felt during the last mile of her hardest marathon while climbing a flight of steps at home, for example, she would probably fall to the floor and call for help, believing she was dying.

Granted, Jenny Barringer was not caught quite so off guard by the suffering she experienced in the 2009 NCAA Cross Country Championships. But Susan Kuijken’s challenge and the discomfort that it provoked in Jenny were surprising enough to make her panic. To be sure, certain elements of her “epic collapse” (to borrow Sean McKeon’s prophetic phrase) were bizarre. The suddenness of her “feeling not so good” and the completeness of her post-collapse recovery had no precedent. We may never understand fully why it all went down the way it did. Nevertheless, the only explanation that makes any sense is Jenny’s own.

“It’s something I set myself up for,” she said.

[velopress cta=”See more!” align=”center” title=”More from the Book”]