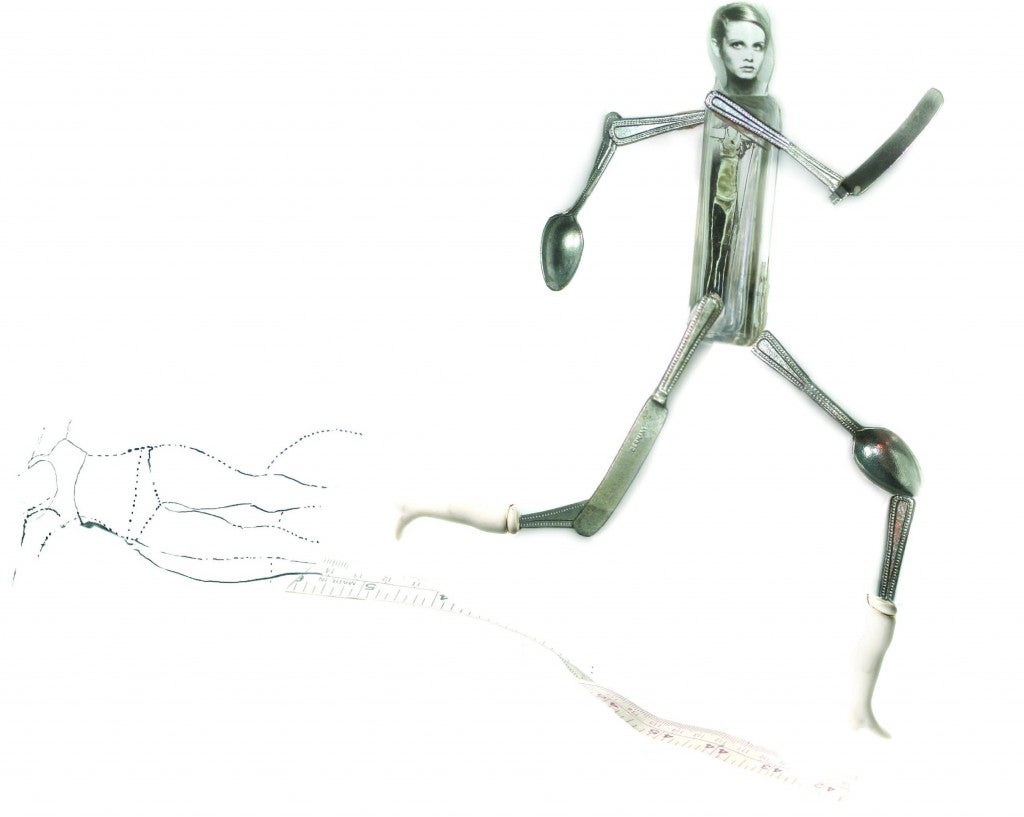

Running on Empty

Growing up, Marya Hornbacher despised running. In junior high, she hated when the coaches made players do laps around the field. But when she went away to boarding school, Marya started waking up every single morning before sunrise to run 5 miles.

Marya’s routine might sound like a healthy new habit —but it wasn’t. When she started running, she was already gripped by a powerful eating disorder, and a fixation on exercise became part of her disease.

“I was very proud of myself for forcing my body to run. And run,” Marya writes in the book Wasted: A Memoir of Anorexia and Bulimia. “Malnutrition precipitates mania. So does speed. Both were at play here, in large doses. But so was masochism…ultimately resulting in a transitory sense of mastery over pain and fear.”

Marya kept upping her mileage as she ate less and less. Soon she was logging 25 miles a day, fueled only by grapefruit and carrot sticks with mustard. When she looks back on that time, more than 20 years ago, Marya now knows running and her eating disorder were intertwined.

“There was never a time where I was running where I wasn’t trying to lose weight,” she says. “I always ran to either lose weight or punish my body in one way or another. If I’d eaten more than I wanted to eat, I ran to punish myself for that. For me, all those things that fed into the eating disorder also fed into the addictive running that I was doing.”

Marya’s experience is not uncommon. There’s an undeniable linkage between weight loss and running. People begin running to shed pounds; elite runners must keep their body fat low to remain competitive; online calculators show how far you need to run to burn the calories you just ate; and the “traditional” runner’s body is rail thin, which means a size that’s unattainable for most individuals is viewed as “normal.”

While running is an effective tool for people who want to lose weight for health reasons, the line between what’s healthy and what’s dangerous for a runner can easily blur.

Dangerous Disorder

When Jackie Bristow was a sophomore in high school, she joined the cross-country team. Her mother, Joan, didn’t know it at the time, but her daughter was also developing an eating disorder. Jackie ran throughout high school and seemed to love the camaraderie of the sport, her mother recalls.

“She was voted the most inspirational on team,” says Joan. “She always had a smile, was always a giving kind of person.”

Jackie went to college in the fall of 2006 but fainted in January of her first year from lack of nourishment. Her parents realized she needed help, so they sent her to treatment. After six months, Jackie was on the road to recovery. But by the following year, she had gone downhill again. On New Year’s Day in 2008, she died.

Joan says she never worried about Jackie’s running and still doesn’t know if it factored into her eating disorder.

“I thought it was a sport that was good for her,” she says. “It didn’t cross my mind that she was using it to keep her weight down. I’ve since found out that a lot of people do that, that it [can be] the same as throwing up.”

Pain Threshold

While running is a healthy habit for the vast majority of women, it can be very destructive in the hands of someone with an eating disorder, says Dr. Cynthia Bulik, the director of the University of North Carolina’s (UNC) Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders.

“Some of the same personality features that are associated with the development of anorexia nervosa are also qualities that may contribute to someone becoming a good distance runner, such as perfectionism, perseverance and the ability to endure pain,” Bulik says.

A runner may start out with a healthy habit like running a few times a week, but then it will transform into an unhealthy extreme.

“For people with eating disorders, the desire to be at low body weight can get completely tied up with their running goals,” explains Bulik. “We have had many people who create narratives for themselves, that their obsessive exercise is really all about their running goals, when in reality it is the eating disorder that is driving them toward unhealthy levels of exercise and obsession.”

Warning Signals

There are some telltale signs that running is part of a disorder, says Evelyn Tribole, a nutrition therapist and author who specializes in eating disorders.

“Are you willing to take days off. Are you willing to fuel your body?” she says. “Do you find you can’t go to a family event or social occasion unless you get a run in? Do you find yourself too worried about what you’re going to eat?”

She says if you find yourself doing well more than what your training program calls for, that can be a sign.

“If you’re getting injured and can’t stop running, that’s a problem,” she says. “Also, if you have changes in mood, irritability and rigidity around eating; if you’ll only eat certain foods or if you’re eating less and less food.”

Running Through It

As a high school runner, Tera Moody seemed to have a promising elite career ahead of her. She was a two-time Illinois champion in the mile and went on to compete for the University of Colorado Boulder in cross country and track.

But her transition to college was difficult, and Moody struggled with depression, anxiety and insomnia. She developed anorexia and dropped from 128 to 96 pounds during her first semester. Although Moody says team pressure, combined with the requirement to wear “itty-bitty uniforms,” may have contributed to her eating disorder, it was more born out of her struggles to adapt to the pressures of college.

Whatever the reason, it damaged her running career. After school, she was forced to take a break from running to work on recovery. Years later, after working to combat her disorder, she decided to train for a marathon and found the distance (and the solo effort) better suited her. She’s since gone on to run in the Olympic Marathon Trials, represent the U.S. in the 2009 World Championships and run a 2:39:10 marathon in Houston last year.

Moody says overcoming her eating disorder was the key to her running success. “I love racing, and know I need to fuel myself to stay healthy and be able to do marathons,” she says. “Everyone sometimes struggles with body image and has days where they don’t feel good. But I remind myself that my best times at races happened when I was at a healthy weight.”

Road to Recovery

Bulik, the director of UNC’s eating disorder center, says experts disagree on whether someone who’s suffered from an eating disorder can continue running—but she thinks it’s possible.

The important thing is that the sufferer works with a psychologist to ensure running remains about health, not weight loss, and consults a dietician to keep nutrition in check. “One trap for many is the obsessional calorie math that can go along with training,” she continues. “If you are finding yourself trying to balance off every calorie you eat with calories expended, you might be entering the danger zone. Remaining mindful of your relapse triggers is critical, and if running feels too high risk, it might be wise to turn to something else for a while in order to solidify your recovery.”

For Marya Hornbacher, author of Wasted, that means never running again. “I tried for a while to keep running as I recovered, but it was like being an alcoholic sitting in a bar and trying not to drink,” she recalls. She does yoga, which allows her to work up a sweat without reverting back to her dangerously competitive drive.

Celebrating Life

A year after Joan Bristow lost Jackie, she worked with her husband and Jackie’s high school cross-country coach to organize a 5K in her daughter’s honor. The race’s theme is “Celebrate Every Body,” and Joan says its goal is to raise awareness about eating disorders so that others can recognize the warning signs before it’s too late.

The race just celebrated its sixth year, and Joan and her husband plan to hold it for as long as they can. “We’re trying to tell people it’s out there, be aware of it,” she says. And experts agree that identify-ing eating disorders early on is the best way to prevent injuries and health issues down the road.

“Talk to your daughters and sons, make sure to tell them to be okay with their weights,” Joan encourages. “We want to let it be known there is no perfect body. Even though an eating disorder will tell you a certain size is perfect, it’s not worth dying for.”

Disorders Defined

Eating issues can come in many forms. Knowing the signs of different disorders will help you identify them in a friend—or yourself.

Anorexia: An eating disorder that makes people lose more weight than is considered healthy for their age and height. Persons with this disorder may have an intense fear of weight gain, even when they are underweight. They may diet or exercise too much or find other extreme ways to lose weight.

Bulimia: An illness in which a person binges on food or has regular episodes of overeating and feels a loss of control. The person then uses different methods, such as vomiting or abusing laxatives, to prevent weight gain.

Binge Eating Disorder: A disorder characterized by recurrent binge eating without the regular use of compensatory measures to counter the binging.

Other Specified Eating Disorder: A disorder that causes significant distress or impairment but does not meet the criteria above. Examples include anorexia that does not bring weight below a normal level, night eating syndrome or purging without binging.

“The commonality in all of these conditions is the serious emotional and psychological suffering and serious problems in areas of work, school or relationships,” says the National Eating Disorder Association. “If something does not seem right, but your experience does not fall into a clear category, you still deserve attention.”

Do You Have a Problem?

- Do you make yourself sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

- Do you worry you have lost control over how much you eat?

- Have you recently lost more than 14 pounds in a three-month period?

- Do you believe yourself to be fat when others say you are too thin?

- Would you say that food dominates your life?

If you answer “yes” to two or more of these questions, you may suffer from an eating disorder. Reach out for help by visiting a doctor, registered dietician, therapist or counselor or by calling the National Eating Disorder Association Hotline at 1-800-931-2237. For more information visit nationaleatingdisorders.org to find treatment options or to chat online.