How to Build a Strong Core Without Sit-Ups

(Photo: Getty Images)

I once believed that sit-ups were the best way to create a strong core, so I diligently did many of them. But my Navasana (Boat Pose) still felt unpleasant. I chalked it up to weak abs and did more and more sit-ups. It wasn’t until I began to study anatomy that I started to understand why this approach wasn’t creating the strong core I was after. Once I started to recognize how abdominal muscles function during movement—and applied this new knowledge—not only was the asana much easier, but I found that I also liked doing it.

Why a Strong Core Matters

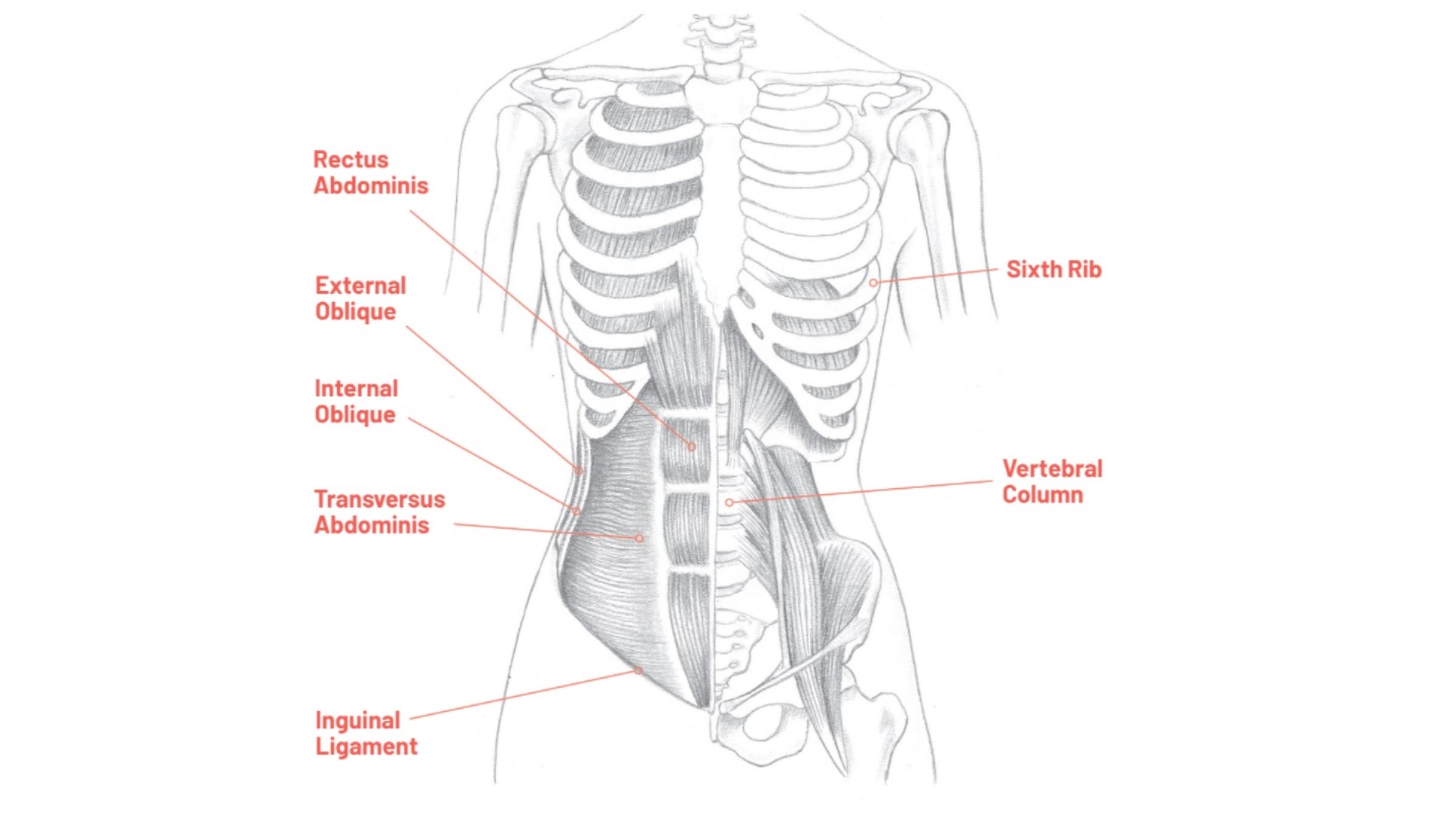

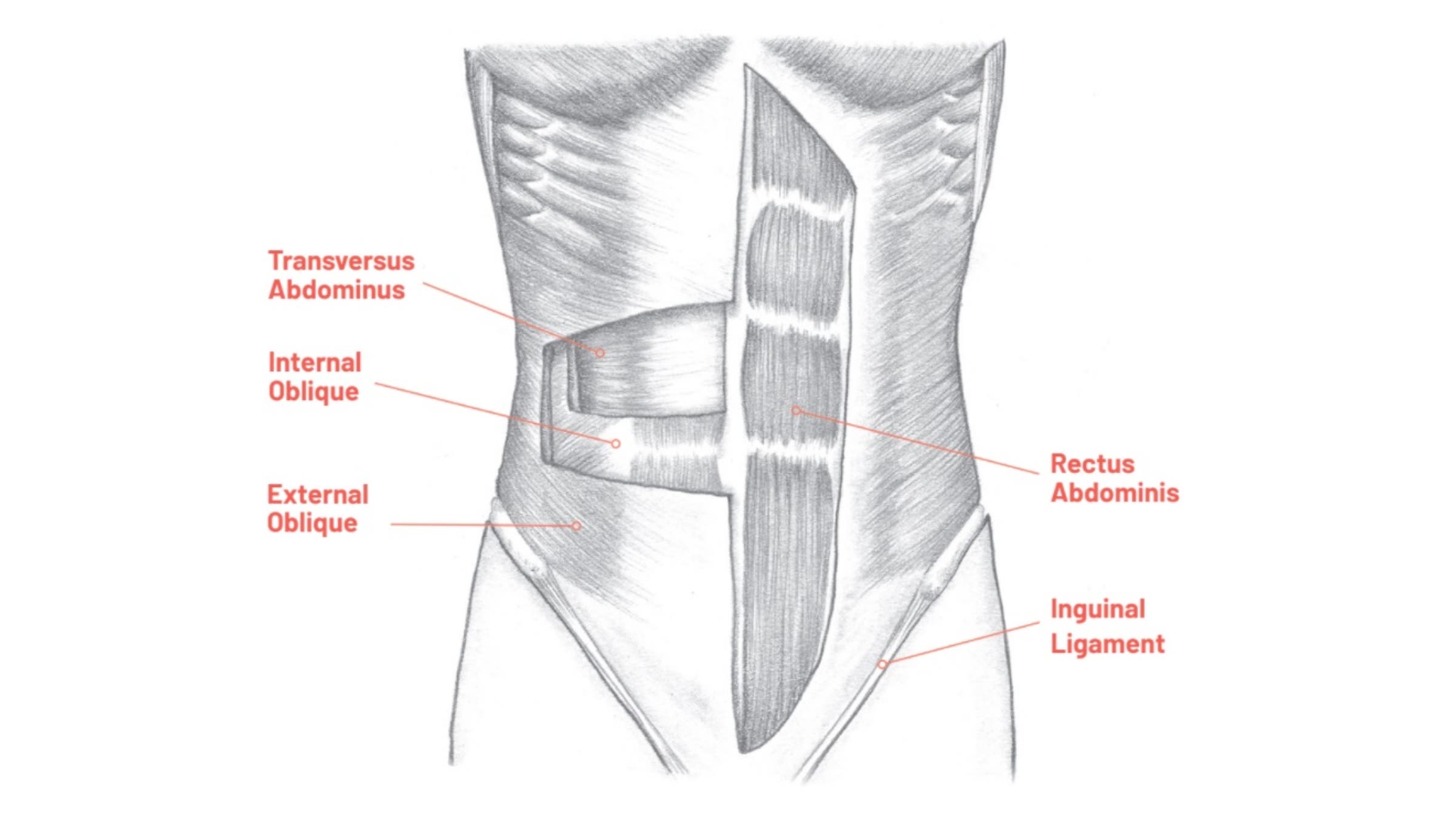

The abdominal muscles stabilize and support the ribs and pelvis (that is, the trunk) and help us stay upright when we stand, lift, bend, or walk. The rib cage and pelvis are connected by the vertebral (spinal) column. Layers of abdominal muscles are connected to these bones and wrap around the front and side of the body in a basket-weave pattern.

Having a strong core is critical, but many fitness instructors give cues that can actually prevent, rather than help, practitioners build strength. I took a spinning class not long ago, and the teacher told us to “pull your abdominal muscles into your backbone and keep them there for the whole class to strengthen your core.” I puckishly thought, “OK, then I won’t breathe!” because the abdominal muscles, when strongly contracted, interfere with breathing. I ignored my teacher’s suggestion, and I observed my abdominals frequently during class.

They seemed to know what to do all on their own. They helped to keep me up on the bike just fine and to exhale strongly when I needed to breathe quickly during challenging points in class.

Structure

There are four abdominal muscles that work together as any team does, with integration and mutual support. The most superficial abdominal muscle is the rectus abdominis. It runs in a straight line up the middle of the trunk, from the pubic bone to the xiphoid process at the lower part of the sternum.

The external and internal oblique muscles make up the next-deepest layers of abdominal muscle. The external obliques are attached to the fifth to twelfth ribs and wrap downward and inward around the middle to attach to the outer iliac crest (the curved upper border of the ilium, the most prominent bone of the pelvis). The right external oblique helps you bend to the right and rotate to the left; the left external oblique does the opposite.

The internal obliques, sometimes called the “same-side rotators,” help you bend and rotate on the same side. In other words, the right internal oblique helps you bend and rotate to the right; the left internal oblique helps you do the same on the opposite side. The final abdominal muscle is the transverse abdominis. It attaches to the cartilage of your lower six ribs, the lumbar fascia (a connective tissue layer that encloses the middle and lower back muscles), the iliac crest, and the inguinal ligament (which anchors the external oblique to the pelvis). Its fibers run horizontally from the back of the body to the front, making it an important stabilizer of the trunk, especially when lifting.

Anatomy in Action

The best way to strengthen the abdominals is to use them as stabilizers. Try the move described below, which works against gravity. Most students find that it becomes challenging much more quickly than sit-ups—and it builds strength faster, too.

Get out your yoga mat, and get into Tabletop position. Place your knees under your hips and your wrists below your shoulders. Lift your right arm so that it is parallel to the floor, with your hand slightly higher than your shoulder. Keeping your arm straight, move your weight slightly forward. You will feel your abdominals contract to stabilize your trunk.

Maintain your breath as you shift a little farther toward the front of your mat. The longer you stay in this position, the more you will feel your abdominal muscles contract. Keep your trunk level, and don’t let your hand drift below the level of your shoulder. Come down as needed when it feels difficult. Then try it with the other arm.

Adapted from Yoga Myths: What You Need to Learn and Unlearn for a Safe and Healthy Yoga Practice by Judith Hanson Lasater © 2020 by Judith Lasater. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, Colorado.

From Yoga Journal