What Researchers Know (and Don’t Know) About Cannabis

(Photo: Jordan Siemens/Getty)

The 2009 Ironman 70.3 World Championship race was supposed to be the race that put Joanna Zeiger in the record books. The professional triathlete and Olympian, who had won the 2008 World Championship event with a world-best time of 4:02:48, was a favorite for a repeat win. If she played her cards right, she could even become the first woman to break the 4-hour barrier for the Ironman 70.3 distance.

She seemed well on her way to these goals as she exited the swim in the front pack and made her way onto the bike course to defend her title. She blazed through an aid station, her right hand outstretched toward a water bottle offered by a volunteer. As soon as she grabbed it, the whole race changed.

“He didn’t let go of the bottle,” Zeiger said. “He just did not let go. He essentially pulled me off my bike, and down I went.”

Zeiger immediately became a blurry tangle of arms, legs, carbon fiber and rubber, tumbling on the pavement for what felt like forever. When everything finally came to a stop, Zeiger scrunched her face and braced herself for what was to come. She was no stranger to crashing—she knew how this worked. Within seconds, an intense, full-body pain set in.

The crash at the 2009 Ironman 70.3 World Championship race was a career-ending one for Zeiger, who sustained a broken collarbone, multiple broken ribs, and permanent nerve damage. Her xiphoid process, an anchor point for the lower ribs, diaphragm, and abdominal muscles, has been surgically removed several times. After each operation, it grows back in the wrong place—rubbing against her heart, pushing down on her diaphragm, exploding into clusters of abnormal bone growth and muscle spasms throughout her ribcage. Sometimes, just breathing can set off a round of muscle spasms.

“Yeah,” Zieger sighs dejectedly after reciting her laundry list of diagnoses. “It just freaking hurts a lot.”

As a professional athlete, Zeiger was used to pushing through discomfort. But constant pain, plus the accompanying nausea and lack of sleep, was almost unbearable. Zeiger tried everything from narcotic painkillers to alternative mind-body practices to get her pain under control (or at least to a tolerable level), and nothing was working. When her husband suggested she try medical marijuana, which had been legal in their home state of Colorado since the year 2000, Zeiger shot him an incredulous glare.

“No,” she replied. “There’s no way I could do that.”

Though she was no longer racing, Zeiger still had the mindset of a professional athlete, and marijuana—even when used medically—was listed as a banned drug by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). She wasn’t about to run afoul of the rules, even if they no longer applied to her. Zeiger’s professional reputation was also at stake in a different way: during her triathlon tenure, Zeiger had also completed her PhD in genetic epidemiology and worked as a researcher at the Institute of Behavioral Genetics at the University of Colorado–Boulder.

“My job was to study drug use and abuse in adolescents and young adults,” Zeiger explains. “At the time, the gateway theory was very popular, meaning that cannabis—what most people know as ‘marijuana’—was a gateway to using harder and worse drugs. That theory has since been debunked, but because of my work at CU, it colored my views on cannabis. It was like this double stigma—one being the professional athlete, and the other working in an environment where it was seen as this nefarious drug. It just never occurred to me during that period that it might actually have good qualities, because all we did was study the negative aspects of it.”

By the time recreational cannabis became legal in 2014, Zeiger’s resistance to the drug had eroded from years of constant pain. Desperate for relief, Zeiger walked into a dispensary and laid out her litany of symptoms. “Do you have anything that can help me?” she asked. The dispensary clerk smiled kindly and slid a package of transdermal cannabis patches across the counter: “This is going to be amazing for your pain.”

That night, Zeiger opened the package from the dispensary, stuck an adhesive onto her skin, and waited. Nothing happened at first. And then suddenly, everything happened.

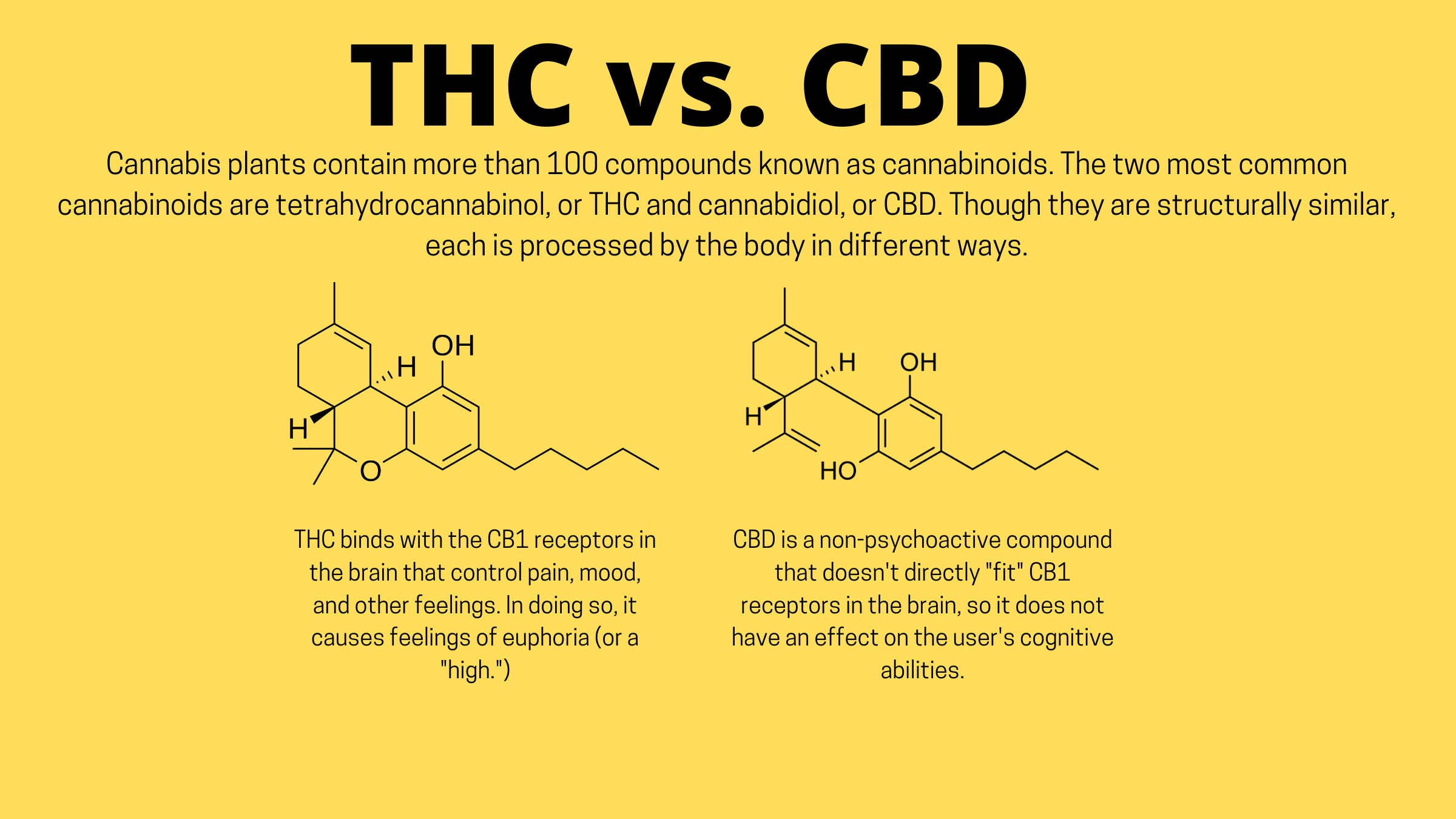

“Nobody explained to me that you need to cut the patch down to smaller pieces,” Zeiger laughs. The patch contained high levels of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the main psychoactive compound in cannabis, and users of such products are typically advised to use small portions (or “doses”) instead of the full patch. “I was so high, it was unbelievable. It was crazy.” She hated the dazed stupor that washed over her—until she realized her pain had subsided significantly. The next morning, she woke up feeling well-rested for the first time in more than five years. Cannabis, as it turned out, might have some good qualities after all.

“Being a researcher, I don’t take one experience and say ‘Well, that’s it. That’s the answer.’ I was willing to use myself as a guinea pig and experiment to see what would be most helpful,” Zeiger said. “I realized there was probably some kind of balance that I needed to find between how much I needed to use to get a good night’s sleep and not having that high that I didn’t like.”

Zeiger began looking into the medical literature on cannabis dosing, but was disheartened by what she found. “There was so little, and it was this huge bias toward the negative aspects of cannabis. To this day, there’s still a very large bias toward studies looking at the negative aspects of cannabis. Being an epidemiologist, I realized I was in a position to take a more neutral look and see how people are using it, whether it’s beneficial.”

She started by talking to people in her social circle—mostly other endurance athletes in Boulder—about their cannabis use, and was surprised to find a fairly widespread acceptance of cannabis use for training and recovery. They talked of using cannabis to reduce pain and inflammation during and after workouts, manage nausea and appetite during ultramarathons, boost recovery through better sleep, and increase their enjoyment of training and racing. “It makes sense, though, because athletes are early adopters,” Zeiger said. “Athletes are very curious about modalities that can improve their performance, their health and wellness, their recovery.”

Zeiger formed an independent research group to carry out the Athlete PEACE Study (Pain, Exercise, and Cannabis Experience), which documented the prevalence and role cannabis plays in the active adult population. Of the 1,161 athletes—mostly triathletes, runners, and cyclists—who participated in the study, 26% indicated they had used cannabis in the past two weeks.

“So I got this answer that athletes are indeed using cannabis [as part of their training and recovery], and now there are so many more questions,” Zeiger said. “How does this work? Does it even work, or is some of this a placebo effect? What dosages are people supposed to be taking, how often, and for what conditions? Why does every person metabolize cannabis differently? How does it impact athletic performance? Is it a performance-enhancing drug?”

Zeiger is one of many researchers trying to find answers to these questions. As more states follow Colorado’s lead in legalizing medical and recreational cannabis, there is an urgency to study the drug’s health effects and understand the best ways to use it in various health, wellness, and medical applications. With growing acceptance of cannabis use by athletes, there are also calls for it to be removed entirely from the World Anti-Doping Association list of banned drugs. Currently, CBD is allowed both in and out of competition. THC is allowed by WADA up to a certain threshold level, but the amount of THC it takes to reach that threshold is different for everyone, which makes it confusing and difficult to use. But athletes use it, nonetheless. In the past 30 years, cannabis has undergone a remarkable transformation from societal scourge to wonder drug.

If the buzz is to be believed, cannabis is a cure-all for just about everything. When CBD became federally legal in 2018, a flood of health and wellness products hit the market, from lotions and tinctures to CBD-infused nail polish and bed pillows. As CBD products became easily accessible, a growing number of runners, cyclists, and triathletes began experimenting with the product as a natural alternative to ibuprofen, naproxen, or opioid painkillers. Some athletes also began to tout it as a sleep aid, recovery supplement, or tool for managing pre-race anxiety.

Its more famous cannabinoid cousin, THC, also gained a reputation as a performance supplement in endurance circles as more states legalized medical and recreational cannabis. In a study of 600 cannabis users living in states where cannabis is legal, four out of five respondents said they use marijuana right before or after exercising. They reported that doing so enhances their enjoyment of and recovery from exercise, and approximately half said it increased their motivation to exercise. Today, news headlines like “How Marijuana Turned Me Into a Distance Runner” and “A Clear-Eyed Take on Running While Stoned” leave readers convinced that cannabis is the solution for every running issue: Hate running? You’ll love it stoned. Painful knees? Use a THC patch—it’s natural, so it’s safer than taking an anti-inflammatory drug. If you get nauseous during an ultramarathon, eat a weed gummy, and your appetite will spring right back.

But none of these claims have been substantiated. In 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cracked down on CBD marketing, issuing a statement asserting that “based on the lack of scientific information supporting the safety of CBD . . . [we] cannot conclude that CBD is generally recognized as safe.” To date, there is no scientific consensus about the safety or efficacy of CBD or THC when compared with anti-inflammatories like ibuprofen or naproxen. Little research on how—or even if—cannabis benefits athletes has been published. In 2018, researchers at McMaster University scoured the literature for studies of marijuana’s effect on athletic performance that included a control group. They found only three small studies, conducted between 1975 and 1986.

In the absence of scientific evidence, athletes have created their own anecdotal database on cannabis. Like hyping up a trendy diet or new pair of super-shoes, members of the endurance community have created a halo effect around CBD and THC, swearing by their n=1 experience as evidence of efficacy.

“As is often the case for controversial treatments with limited evidence bases characterizing their effectiveness, zealotry permeates discussions of their merits, limits, and downsides,” Drs. Daniel Carr and Michael Schatman wrote in a 2019 article on cannabis for pain management in the American Journal of Public Health. “Uncritical enthusiasm of ‘medical marijuana neuromysticism’ among both users and empirical investigators has slowed rigorous evaluation of its risks and benefits, contributing to cannabis’s failure to become a legitimate medicine.”

That’s not to say the anecdotal evidence is invalid, or that the majority of runners are simply experiencing a mass placebo effect. There just isn’t enough science to back up those claims.

But the science isn’t so easy as just getting athletes high and putting them on a treadmill. To study cannabis in sport is to navigate an obstacle course of controversy, contradiction, and a maddening tangle of red tape.

“It’s all political,” Dr. Gretchen Maurer cuts right to the chase when I ask about the challenges of studying cannabis. “It has been since 1937 [when federal regulation of marijuana began]. The biggest problem we have in understanding cannabis is the fact that our government puts cannabis right up there with drugs like heroin and LSD.”

Though marijuana is legal by a doctor’s order in 47 states and recreationally in 11 states (with five more states voting on legalizing marijuana this fall), it remains in the same class federally as heroin and LSD—a Schedule I drug, designated as having “a high potential for abuse” and “no currently accepted medical use.” At the federal level, marijuana is considered more dangerous than prescription opioids like oxycodone and fentanyl, which are classified as Schedule 2 drugs, despite being responsible for epidemic levels of overdose illness, injury, and death. (In contrast, there is no evidence that overdose of cannabis can cause death. The United States Centers for Disease Control has described the risk of a fatal overdose of marijuana as “unlikely.”)

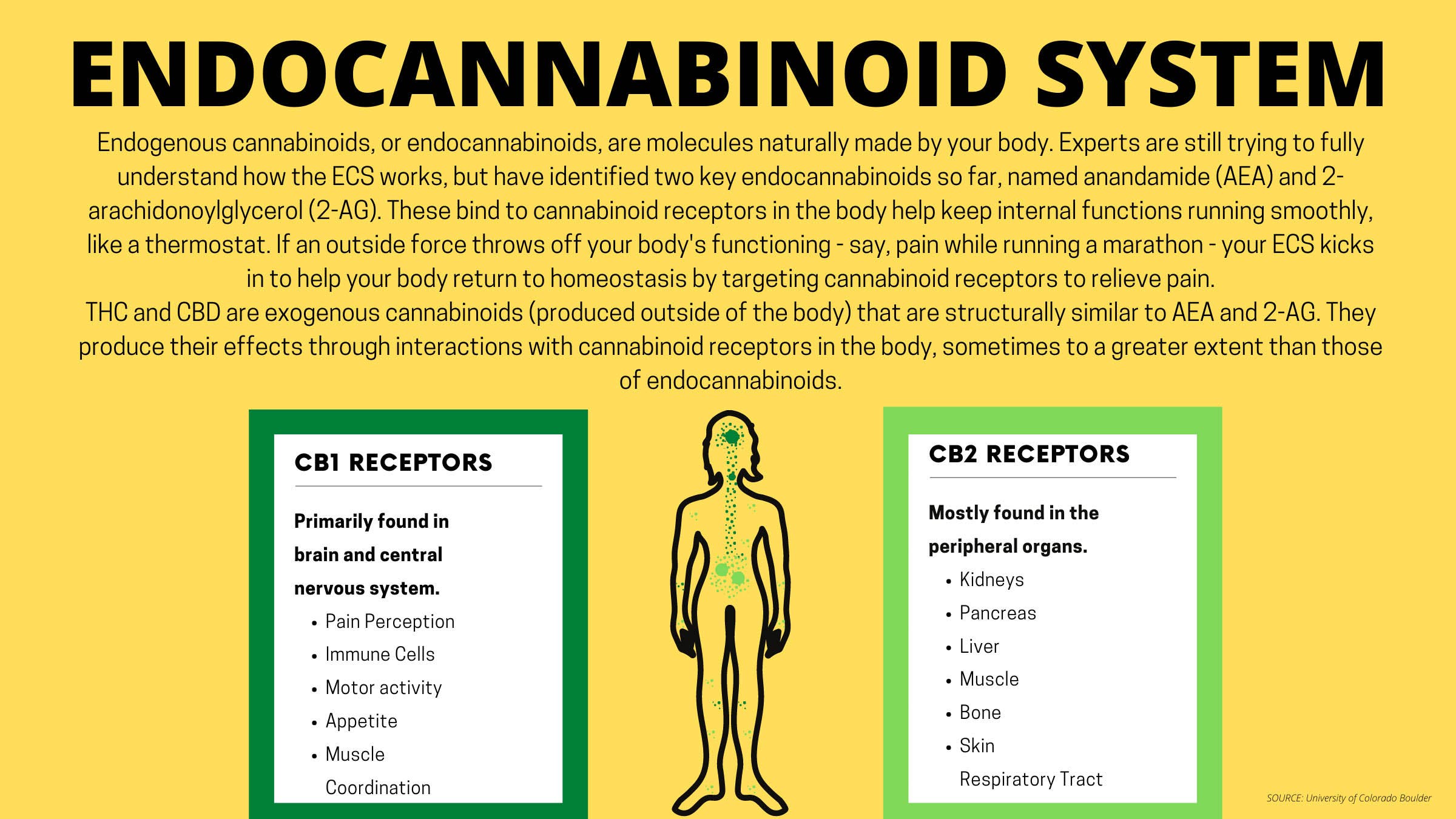

Pain is a specialty for Maurer, a physician and cannabis researcher in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Prior to medical school, she completed her master’s thesis on chronic pain and ways to reduce the use of opioids in managing pain. Her mentor in medical school, who was also passionate about pain management, made it a point to teach students about the endocannabinoid system, or receptors in the nervous system that maintain homeostasis in the body. The discovery of the endocannabinoid system is fairly recent, and experts are still trying to fully understand it. Still, there are indications that it plays a major role in regulating inflammation and pain.

“The endocannabinoid system is not that well represented in medical education, so I feel I was privileged in that way to learn about it medically. A lot of physicians are really unaware of the endocannabinoid system and how its modulation might benefit patients who are in pain,” Maurer said. “It’s really fascinating how our bodies have this whole endogenous system that has far-reaching implications on our perception of pain.”

Wanting to investigate further, Maurer followed up her medical school training with a year-long graduate certificate course in Cannabis Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. In this first-of-its-kind program, health practitioners learn of what is known about cannabis therapies for specific medical conditions; perhaps just as equally, they learn what’s not known.

“There’s a lot of qualitative data about cannabinoids and cannabinoid therapies,” Maurer explains. “But qualitative data doesn’t hit the power of quantitative research. The gaps are just evident in the fact that we just have limited high-quality, randomized, double-blind, controlled trials that are ultimately needed for recommendations by clinicians.”

Even Maurer’s own research into cannabis applications for sports medicine has so far been conducted without a laboratory. Her 2020 article published in the journal Sports Health was a literature review of preexisting research titled “Understanding Cannabis-Based Therapeutics in Sports Medicine.” It concluded there is no understanding of cannabis-based therapeutics in sports medicine: “Lack of strong-quality clinical evidence, coupled with inconsistent federal and state law as well as purity issues with cannabis-based products, make it difficult for the sports medicine clinician to widely recommend cannabinoid therapeutics at present.”

“It’s almost impossible to do a clinical trial with cannabis,” Maurer remarks before launching into the complex regulatory hoops required to even be able to study the drug in the United States: reviews by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); building a lab with strict storage requirements for the cannabis product (including an alarm, a lock, and a container physically attached to the floor and wall); restrictions on the amount of cannabis a researcher can obtain; piles of paperwork documenting when, how, and by whom the cannabis was used.

And then there’s the product itself. “It’s just really pathetic,” Maurer groans. “The quality of the cannabis the government grows for research is unrecognizable compared to what’s available in dispensaries to patients.”

Since the late 1960s, the marijuana research lab at University of Mississippi’s School of Pharmacy has been the only facility in the United States permitted by the federal government to cultivate cannabis for research purposes. Researchers have been critical of the product from the site, saying the plants cultivated are weak strains from the 1970s and arrive at labs covered in mold. While the DEA opened production to other growers in 2016, none have yet been able or willing to comply with the agency’s regulatory requirements. This limits researchers to low-quality plants and products that are much lower in THC than what consumers can buy at a dispensary.

“It doesn’t represent the ratio of cannabinoids that we’re interested in looking at,” Maurer said. “Cannabis is really so broad. There’s hundreds of cannabinoids, and they’re all different. Through years of breeding, every cannabis plant, every cultivar is different, and you can’t patent a plant. When patients go to a dispensary, it’s like a free-for-all. Who knows what they could come out with?”

Currently, there are more than 700 identified strains of cannabis, each with varying chemical components. This diversity isn’t reflected in the limited product line from the University of Mississippi, and limited research can lead to even more limited findings. A clinical study might conclude a certain condition does not respond to cannabis-based therapeutics, when in actuality the condition might just respond to a different strain with a different formulation. Zeiger’s PEACE study of athletes, for example, found that athletes who used THC in combination with CBD reported the most beneficial effects for pain relief, appetite, and restorative sleep when compared to than those who used CBD or THC alone—a phenomenon known as the “entourage effect” in cannabis research. But to even confirm this, much less ascertain what ratio of THC to CBD is ideal for athletic recovery, a clinical study with various strains would need to be conducted. Currently, that kind of controlled study can’t be done with federally-grown cannabis.

Even the most ardent cannabis researchers find the process of jumping through regulatory hoops exhausting, and many give up, saying they’ll wait until cannabis is legal at the federal level and therefore easier to study. But it’s not clear when—or if—that will happen. In the interim, some cannabis researchers are finding legal loopholes to get the job done.

In Boulder, Colorado, there is no shortage of runners, cyclists, or triathletes. There is also no shortage of people who use cannabis. A long-running joke in the town is that a Venn diagram of those two demographics is not a staggered overlap, but a perfect circle. In short, if you want to study the impact of cannabis on endurance athletes, you should probably do it in Boulder.

Dr. Angela Bryan, a psychology researcher at CU Boulder, was eager to set up such a lab when recreational cannabis became legal in the state in 2014. “My whole career has been spent studying health and risk behaviors. When the state of Colorado legalized, that really opened up the opportunity for us to start looking more broadly into cannabis and the implications of public health,” Bryan explains. “Because up until that point, almost all of the research that had been done was looking at it only as a risk behavior. But there was also this general understanding that some people were getting benefits. I thought this would be a great opportunity to finally get some answers.”

But Bryan soon found out easy access to cannabis research wasn’t so easy after all. Though medical and recreational cannabis is legal in the state of Colorado, CU Boulder is a drug-free zone. In compliance with the federal Drug Free Schools and Communities Act, the campus must prohibit the manufacture, dispensation, possession, use, or distribution of any controlled substance, in any amount, on its grounds.

“We are not allowed to touch it, we’re not allowed to have it in our lab, we’re not allowed to randomly assign participants to take different things, as you would in a traditional randomized controlled trial,” Bryan said. “Essentially, the Drug Free Schools and Communities Act says that if a school is in violation of the act, they lose their federal funding. So if I bring somebody into my lab and have them use cannabis in my lab, I’ve now essentially violated the Drug Free Schools Act,” Bryan explains. “In theory, the government could say, ‘Your campus gets no more federal funding.’”

In 2018–2019, the University of Colorado system received a total of $771 million in federal research awards, so to lose that funding—over studying a bunch of stoners, no less—would be catastrophic. At first, Bryan resigned herself to qualitative research and indirect study designs, like so many before her. But when the data returned, she knew she had to do more.

“I was working with a graduate student named Ariel Gilman on a study to determine if cannabis use was a possible risk or benefit in the obesity/diet/exercise equation,” Bryan said. “Because when people consume cannabis, they have a tendency to overeat things that are not good for you. There’s that tendency to experience couch lock, or extreme sedentary behavior. So we thought, ‘gosh, this could potentially have harmful impacts on the obesity epidemic.’”

But as they began to dig into the research, they were surprised to discover that people who use cannabis seem to have a lower body mass index (BMI), a healthier hip-to-waist ratio, and lower incidence of type two diabetes. “It was the exact opposite of what we thought we would find,” Bryan said.

Their search for an explanation took them down the rabbit hole of cannabis use in the endurance sports world. Bryan and Gilman, who are both avid runners, uncovered enough anecdotal evidence to convince them the study of cannabis as an ergogenic aid was worth the effort. “We started thinking about what impact does cannabis have on facilitating exercise? Why might that be? What is it about cannabis that keeps people going? We really wanted to understand the mechanistic factors.”

CU Boulder was on board with the idea of studying cannabis in a controlled clinical fashion, but extremely cautious about violating the Drug Free Schools Act. For four years, Bryan and her research partner, neuroscientist Dr. Kent Hutchison (who is also Bryan’s husband) went back and forth with the legal team at the University of Colorado to find a way to study cannabis. At first, all proposals, like setting up an off-campus laboratory, were nixed by the lawyers and administration. There were just too many risks. With their options dwindling, Bryan admits their ideas took a turn for the ludicrous—when she threw out the idea of creating a mobile lab in the back of a van, she did so as a joke. The lawyers were intrigued, though. If it was done right, it could work.

The mobile lab design fit through just enough legal loopholes to satisfy both the school and the federal government. Legally, Bryan can’t bring study subjects to a CU lab and have them use cannabis, but she can bring the lab to people who are already using cannabis of their own accord. The two Sprinter vans, procured in 2017 and lovingly named the “CannaVans,” now travel around the Boulder metro area in pursuit of data.

Conducting research in the CannaVan is a bit more complicated than studying a traditional subject in a traditional lab, to be sure. CannaVan scientists can’t buy or distribute the cannabis, so study participants have to obtain it on their own. When the van shows up, the participants enter sober and run through a battery of tests, including blood draws, cognitive evaluations, balance challenges, and more. Then they enter their homes, get as high as they want, and return to the van for the same tests. In studies involving exercise, the sober/high experiments also include treadmill tests where physiological data is collected alongside self-reported assessments, like rate of perceived exertion (RPE) and perception of time.

The research protocol is far from perfect. There is no standardization for potency or chemical composition, so there is individual variability for the product used; researchers can’t give their participants direction on what product to buy or even what dispensary to use to buy it. The researchers also can’t control the dose of cannabis, nor can they dictate how a participant consumes it. Because researchers are limited to studying one person at a time in the van, they have to wait for the drug to take effect. Inhalation methods (vaping or smoking) are the fastest, while edibles can take hours to digest and take effect, so Bryan and her team can sometimes spend hours waiting to conduct their tests. They can’t take any product used by their participants back to campus to test the purity or chemical composition of the product.

But through this restrictive, complicated, and time-consuming protocol, they are inching closer toward getting some answers, and some answers are better than none. “More often than not, our research participants want to know the answers to these questions as much as I do,” Bryan said. “Is cannabis good for exercise or bad for exercise? Are the effects they’re feeling real or imagined? Is it safe to keep doing what they’re doing?”

Cannabis culture has a decades-long head start over cannabis science. With every new CBD or THC product touted by endurance athletes, the gap grows ever larger between how much we use and how little we actually know. Surveys and anecdotal reports can be pieced together to create a best guess of the biological mechanisms by which cannabis may affect physical activity, but until more rigorous testing can be done, there’s no way to know for sure.

“We have ideas, like maybe CBD is the part that helps with pain during exercise. Maybe THC is the part that helps make running a more positive experience. Maybe some combination of the two might be best. We don’t know,” Bryan said. “We need to have objective assessment and controlled studies to get those answers.”

Barriers to conducting comprehensive research mean physicians like Maurer can’t make recommendations regarding cannabis that are rooted in evidence. If Maurer prescribes an anti-inflammatory medication for a running injury, she can give a specific dose based on the clinical studies that confirm X milligrams of Y drug is safe and effective for Z condition. When a patient comes to her with questions about using cannabis, the process isn’t so straightforward.

“As a physician, my job is to advocate for the patient and provide them with options, so they can make informed decisions about their health. You can argue that a lot of people who use cannabis are self-medicating. When people are in pain or can’t sleep, they feel out of control, and this helps give people a sense of control. In medicine, we need the evidence so we can recommend treatment in a safe and therapeutic way. How can we get you to a level of function where, despite having arthritis, we can manage your pain so it’s tolerable to go out for a run?”

Bryan agrees: “I would love to be able to get to the point where someone says, ‘I would love to run a 10K and have it feel better,’ and we will say, ‘Oh, well then you should take a one to one five milligram gummy like 30 minutes before.’ We don’t have the ability to make those recommendations right now. The science just isn’t there.”

Until then, cannabis science is a collaborative effort, where athletes can take an active role in discovering what works and what doesn’t, and scientists can use these discoveries to guide their research. Zeiger says one of the most exciting things about this unique time in the United States is that with the turning tide of legalization, users can experiment with products to fit their needs. Athletes are at a particular advantage in this self-experimental process, as they are usually quite observant when it comes to their own bodies and can provide detailed insights that can be valuable to the scientific process.

“One of the most wonderful things about cannabis is that each person is in control of their destiny. If you go to the doctor and get a prescription for something, you have to take the dose they give you. If you need to change that dose, you’ve got to go back to the doctor, and it’s a whole thing,” Zeiger said. “But cannabis patients are in control, because they can do their research, then buy what they feel might work for them, whether it’s CBD, THC, or a combination. If the first thing doesn’t work, they can try something else until they find the product that is right for them.”