Book Excerpt: Life's Too Short To Go So F*cking Slow By Susan Lacke

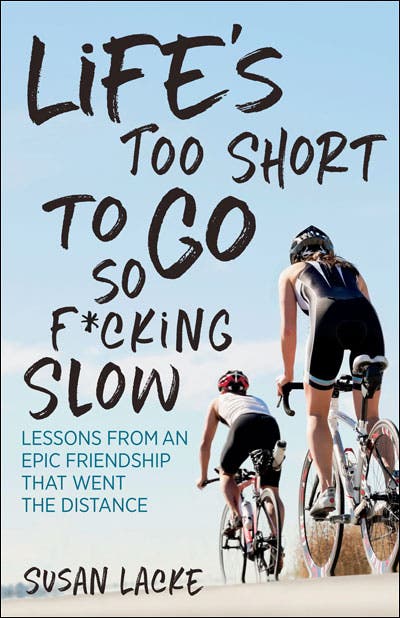

Life's Too Short to Go So F*cking Slow by Susan Lacke

Book excerpt published with permission from VeloPress.

This is an excerpt from Life’s Too Short To Go So F*cking Slow, a personal memoir by sports writer Susan Lacke that explores a deep but unlikely friendship that traversed life, sport, illness, and everything in between.

VERY DUMB THINGS

It was one of those days.

Because I had forgotten to set my alarm the night before, I didn’t wake up until almost 9:00 in the morning. Because I had gotten such a late start, I was riding my bike during the hottest part of a stifling summer day. Because I was riding my bike in the heat of the day, I was depleted. Because I was depleted, I was grumpy.

And because I was grumpy, I was not in the mood to deal with Carlos’s shit.

And yet I had no choice. In my flustered rush to get out the door that morning, I had forgotten to grab spare tubes for my tires. I didn’t realize my mistake until I was 40 miles out of town on a deserted road lined with puncturevine weeds. Their gnarly thorned seeds littered the road, creating a perilous obstacle course for my thin rubber tires. When I felt the telltale thunk-thunk-thunk of a flat, I plunged a hand into my jersey pocket and cursed as I realized my mistake.

I really didn’t want to text Carlos for help. One of the first things he’d done after I bought my bike was teach me how to change a flat tire, stressing that I always needed to be prepared and self-reliant. “Nobody likes to rescue a dumbass,” he’d repeat on a loop. “Never leave the house without water, food, or flat kit.”

That day, I had only two of the three on my bike. I used my cell phone to text everyone I knew except Carlos, hoping someone would be willing to pick me up—but the replies ranged from “Busy” to “No car” to “You rode your bike to where?”

I considered my options: I could walk to the nearest gas station, more than 15 miles away, or I could wait for a car to appear on the desolate road, thumbing for a ride from a potential serial killer. Or I could text Carlos and admit that I had messed up. I looked up at the scorching sun and wondered if there was any benefit to befriending a serial killer.

An hour later, a black car appeared on the horizon, slowing to a halt upon seeing me on the side of the road. A tinted window rolled down, and the driver leaned across the passenger seat to take stock of the disabled bike and sunburned rider.

“For someone so smart, you really do a lot of very dumb things.” Carlos sighed, unlocking the passenger door to let me in.

“I’m not in the mood, sir.”

“What did I tell you? Never leave the house without—”

“Not. In. The. Mood,” I hissed. Carlos reached into the backseat and handed me an ice-cold bottle of water.

I never left the house without a flat kit again. But unfortunately, that wasn’t the last time Carlos had to rescue me from very dumb things.

I was dumb tons of times, like when I read in a cycling magazine that losing weight would make me faster on the bike. I cut my diet down to a thousand calories per day, hoping a quick weight loss before that weekend’s ride would make it easier to stay with the group without getting dropped. I lost five pounds before that Sunday and felt like I had won—I was smart. But when we started riding that morning, my legs suddenly felt and behaved as if they were made of concrete. Carlos pulled me from the ride, took me to Starbucks, and stuffed me full of whipped-cream mochas and maple-glazed scones until I felt like a human again. A very dumb human.

I was dumb when I declined Carlos’s invitation to join a group of friends for a monthly practice swim in a local lake. “I prefer the pool,” I said, and it was true. The pool was clean and the lanes well marked; I felt safe and capable there. It was the smart thing to do.

But the pool didn’t fully prepare me for my first triathlon, a local sprint-distance race in which I entered the murky waters of the lake and proceeded to panic in spectacular fashion: Why are these people so close to me? Where’s the black stripe on the bottom? Why can’t I see my hand in front of my face? What is that thing floating up from the bottom? That’s a lake zombie. Oh, my gosh, that is a lake zombie! I popped up in the water, frenetically doggy-paddling and gasping for air.

“Lake zombie!” I screamed. “Lake zombieeeeeeeeee!” Carlos, who was watching from the sidelines, doubled over with laughter.

I was dumb on my first century ride, during which Carlos yelled over his shoulder a reminder to eat and drink every 30 minutes. I rolled my eyes and retorted that I had things under control, thankyouverymuch. I didn’t feel hungry, so I didn’t eat, and—as I learned at mile 60—I didn’t have things under control at all. Even then, I faked a smile and told him I was feeling fine despite the mental chatter blaring in my panicky, calorie-depleted brain: This is it. This is how I’m going to die, in the middle of the desert wearing neon spandex. Carlos, recognizing a bad bonk when he saw one, called for a break at the next gas station, where he silently handed me a cola and a bag of potato chips. It was unspoken yet clearly understood: I’d done a dumb thing.

I was very dumb two weeks before Ironman Wisconsin, when a nagging cold turned into a sore throat, which turned into an inability to swallow. I thought I was being smart by continuing to train, because I could sweat the illness out of my body through exercise.

One day after swim practice, Carlos suggested that we go out for frozen yogurt to soothe my inflamed throat. I jumped into his car with excitement, and he drove us a mile down the street and parked.

“This isn’t the froyo shop,” I stated, pointing at the brick building in front of us.

“Nope.” Carlos got out of the car, opened my door, and gestured for me to follow him into the urgent care clinic. He did eventually take me for froyo—after the doctor diagnosed me with strep throat and wrote a prescription for antibiotics.

Even when he wasn’t physically present, Carlos would still find a way to alert me when I was doing a dumb thing. When race day finally came around for Ironman Wisconsin, I did everything perfectly: I ate all the right things, did all the right warm-ups, and entered the water at exactly the right time. I paced myself well on the swim, fueled at the appropriate intervals on the bike, and started the run feeling strong and fast. I was dominating. I was smart!

In the early miles of the run leg, I saw my mom standing on the sidelines. With a concerned look, she waved me over to the curb and broke into a jog alongside me.

“Carlos says you’re going too fast right now!”

“What are you talking about?”

She waved her cell phone in the air. “I’m on the phone with him right now. Carlos is tracking you online. He says you’re going out too fast and that you’ll pay for it later. Slow down!”

My jaw dropped in shock. How had he gotten my mother’s phone number? “Tell him I’ve got this under control.”

“He said you’d say that,” she shouted as I pulled away to rejoin the main pack. “Don’t be a dumbass!”

As I ran off in pursuit of the finish line—this time at a slower pace—I couldn’t help but laugh.

Related:

Book Excerpt: The Anxious, Excited Thoughts Of An Ultrarunner

Shaz Kahng Delivers A New Kind Of Female Hero In “The Closer”

Book Excerpt: The Moment I Decided To Run A Marathon

[velopress cta=”See more!” align=”center” title=”About This Book”]